Greenville

Auf der Walnut Street fanden wir auch jemanden, der seit Jahren eine alte Zeitungsfabrik sein Zu Hause nennt. Als Junge hat er für ein paar Cent die Zeitungen morgens bei der Fabrik abgeholt und verkauft. Heute ist es seine Werkstatt und Museum zugleich. Er sammelt alles was der Mississippi her gibt. Und zuerst wollte ich es nicht glauben, aber er fand auch Dinosaurier-Eier! Hier ein paar seiner Fundstücke.

Henry Townsend - Shelby

"Henry Townsend, the only blues artist to have recorded during every decade from the 1920s to the 2000s, was born in Shelby on October 27, 1909. A longtime resident of St. Louis, where he was hailed as a patriarch of the local blues scene, Townsend died on September 24, 2006. Other performers from the Shelby area have included singers Erma Franklin, Jo Jo Murray, the Kelly Brothers, and Hattie Littles, jazz legend Gerald Wilson, and bandleader Choker Campbell.

Townsend, a master guitarist and pianist, played an integral role in the vital St. Louis blues scene of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. His earliest years were spent in Shelby and then near Lula; the family was in Cairo, Illinois, when Townsend ran away from home and settled in St. Louis as a preteen. He made his recording debut in 1929, and during the 1930s he recorded in the company of leading blues artists including Roosevelt Sykes, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Robert Nighthawk, and Mississippi-born Big Joe Williams and Walter Davis. A prolific and spontaneous composer, Townsend claimed credit for writing the first version of the blues standard “Every Day I Have the Blues,” recorded by Tupelo native Aaron “Pine Top” Sparks in 1935.

Townsend continued to record with Davis after World War II but began working more outside of music as a hotel manager and debt collector. In 1961Townsend recorded his first album for folklorist Sam Charters, and over the next decades he toured, recorded several albums, and mentored younger artists in St. Louis. He received a prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1985. In 2008 he was awarded a posthumous Grammy for his participation on the album Last of The Great Mississippi Delta Bluesmen - Live in Dallas, which featured fellow nonagenarians Robert Lockwood, Honeyboy Edwards, and Pinetop Perkins.

Shelby was also the birthplace or childhood home of a number of performers who achieved later fame in Detroit, Chicago, and California. Erma Franklin (1938-2002), older sister of Aretha Franklin, recorded the first version of “Piece of My Heart,” later popularized by Janis Joplin. Singer Hattie Littles (1937-2000), once billed as the “New Queen of the Blues,” and saxophonist-bandleader Walter “Choker” Campbell (1916-1993) both recorded for the Motown label group in Detroit. Trumpeter-bandleader Gerald Wilson (b. 1918) became an elder statesman of West Coast jazz after decades in the Los Angeles area. The Chicago area was the destination of the Kelly Brothers and their cousins, the Johns Brothers, as well as singer-guitarist Gus “Jo Jo” Murray and blues singer-bassist Willie Kent. Andrew (1935-2005), Curtis (b. 1937), and Robert Kelly (b. 1939) recorded gospel music and rhythm & blues and were billed both as the Kelly Brothers and the King Pins. Tenry “T. J.” Johns (b. 1946) led the band T. J. and the Hurricanes in Shelby and later recorded in Chicago under the name “The King Kong Rocker.” Kent (1936-2006), a favorite figure on the Chicago blues scene, recorded several albums and won numerous Blues Music Awards. Jo Jo Murray (b. 1947) remained a familiar figure in Shelby with frequent homecoming appearances at local clubs." (content © Mississippi Blues Commission)

Shaw

Honeyboy Edwards - Shaw

"David "Honeyboy" Edwards, born in Shaw in 1915, took to the road as a teenager accompanying Big Joe Williams and became a true "rambling" bluesman. Later Edwards traveled with other artists, including Robert Johnson. Edwards recorded blues for the Library of Congress and the Sun and Chess labels, but he is also revered for his colorful tales of the lives of early Delta bluesmen.

David Edwards, nicknamed "Honeyboy" by his sister, was born in Shaw on June 28, 1915. He started playing guitar at age twelve, learning from his father, Henry Edwards, and as a teenager from pioneer bluesmen including Tommy Johnson and Charley Patton. In 1932 bluesman Big Joe Williams took Edwards under his wing, teaching him valuable lessons about how to survive on the road. Edwards later traveled widely, often as a hobo on freight trains, skillfully avoiding arrests for vagrancy. He became a good gambler, and often played blues for tips until he made enough to enter games. Edwards described the life of the itinerant bluesman, relaying both its joys and difficulties, in his 1997 autobiography The World Don't Owe Me Nothin'.

In 1937-38 Edwards worked with Robert Johnson and attended Johnson's final performance in the Greenwood area in 1938, when Johnson was allegedly poisoned. Other artists he worked with in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Memphis included the Memphis Jug Band, Big Walter Horton, Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), Tommy McClennan, and Little Walter Jacobs.

In 1942 Alan Lomax of the Library of Congress recorded Edwards in Clarksdale, and in 1951 Edwards made his first commercial recordings in Houston, Texas, for the ARC label as "Mr. Honey." He also recorded for the Sun and Chess labels in the '50s, but the sessions were not issued until the 1970s. In 1956 Edwards settled with his wife in Chicago, where he found work as a laborer and performed with Big Walter, Carey Bell, and others. In 1969 he was a guest on an album by the British band Fleetwood Mac and over the subsequent decades recorded many albums on Folkways, Earwig and other labels. Edwards’s charming personality, storytelling skills, and memories of early blues artists were captured in the 2002 documentary Honeyboy, which included footage filmed in Shaw.

Most blues activity in Shaw over the years has been in juke joints such as the White House, the Riverside Inn, the One Minute, and Fox's, although small local blues festivals have been held on occasion since the 1990s. Shaw was also the birthplace of Louis Satterfield (1937-2004), a prominent studio musician for Chess Records in Chicago and trombonist with the group Earth, Wind & Fire, and of Clarksdale guitarist and Delta Blues Museum educator Michael "Dr. Mike" James (b. 1965)." (content © Mississippi Blues Commission"

Leland

Leland ist nicht nur die Geburtsstätte von Jim Henson, sondern auch die Geburtsstätte vom berühmtesten Frosch der Welt.

|

| Cat of the Day |

Highway 61 Blues Museum. Leland

Son Thomas - Leland

James Henry “Son” Thomas, internationally famed blues musician and folk sculptor, worked as a porter at the Montgomery Hotel, which once occupied this site, after he moved to Leland in 1961. Born in the Yazoo County community of Eden on October 14, 1926, Thomas made his first recordings for folklorist Bill Ferris in 1968. He later traveled throughout the United States and Europe to perform at blues concerts and exhibit his artwork. Thomas died in Greenville on June 26, 1993.

Thomas was one of the most recognized local musical figures in Mississippi during the 1970s and ’80s. He performed throughout the state at nightclubs, festivals, private parties, government social affairs, colleges, and juke joints. He also toured and recorded several blues albums in Europe, and his folk art was featured at galleries in New York, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Thomas learned guitar as a youngster after hearing his grandfather, Eddie Collins, and uncle, Joe Cooper, at house parties in Yazoo County. He later saw the two blues legends he regarded as his main influences, Elmore James and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, as well as Bentonia bluesman Jack Owens, from whom he learned the song “Nothin’ But the Devil.” After he began playing jukes with Cooper, Percy Lee, and others, Thomas became so well-known for his rendition of the Lil’ Son Jackson tune “Cairo Blues” that he earned the nickname “Cairo.” He was also known as “Sonny Ford,” so named for his childhood fondness for making clay models of Ford tractors.

In 1961, with a wife and six children to support on a sharecropper’s income, Thomas decided to move to Leland to find better-paying work. His mother got him a job at the Montgomery Hotel where she worked, but soon Thomas joined his stepfather as a gravedigger and later worked at a furniture store. His performances had been confined to juke joints and house parties until he met Bill Ferris, who began recording and filming Thomas and other local bluesmen in 1968. The Xtra label in England released the first recordings of Thomas, who later made albums for the Mississippi-based Southern Culture, Rustron, and Rooster Blues labels as well as companies in France, Holland, and Germany.

He also appeared in several documentary films. Despite his international renown and increased income, Thomas continued to lived in bare, dilapidated shotgun houses. It fit his image, he said, knowing that blues fans, art buyers, and photographers would come looking for him. The most important place for him to earn his living was often not out on the concert circuit but at his house, where visitors would show up at his doorstep with money to hear him play or buy a skull or coffin he had sculpted. Thomas’s gaunt appearance and the deathly themes of much of his artwork led to neighborhood rumors that he was a “hoodoo man.” But his magic lay in his ability to purvey his art and music, and his songs and stories were permeated by a droll sense of humor rather than darkness. His son Raymond “Pat” Thomas earned his own niche as an authentic bluesman and folk artisan, especially noted for his drawings of cats’ heads. (content © Mississippi Blues Commission)

Lothar überreichte Pat Thomas Fotos von seinem Vater, die er bisher nie gesehen hatte. Die Fotos entstanden in den 80er Jahren beim American Folk Blues Festival. Die Bilder von Lothar könnt ihr hier finden: http://www.gig-photos.de/american-folk-blues-festival-1982/

Cleveland

|

| Casts of Blues Mask - Ewing Hall Delta State University Cleveland, MS 38733 |

Merigold

Po' Monkey's - Merigold

The rural juke joint played an integral role in the development of the blues, offering a distinctly secular space for people to socialize, dance, and forget their everyday troubles. While many such jukes once dotted the cotton fields of the Delta countryside, Po’ Monkey’s was one of the relatively few to survive into the 21st century. Initially frequented by locals, Po’ Monkey’s became a destination point for blues tourists from around the world during the 1990s.

According to Willie “Po’ Monkey” Seaberry he opened a juke joint at his home in this location in 1963. Seaberry (b. 1941) worked as a farmer and operated the club, where he continued to live, at night. By the 1990s Po’ Monkey’s was attracting a mixed crowd of locals as well as college students from Delta State University and blues aficionados in search of “authentic” juke joints. The dramatic décor both inside and outside the club also attracted attention from news outlets including the New York Times and noted photographers including Annie Leibovitz and Mississippi’s Birney Imes, who featured the club in his 1990 book Juke Joint. Despite such notoriety Po’ Monkey’s in many ways continued to typify the rural juke joint, furnished with a jukebox, a pool table, beer posters stapled to the walls, and Christmas lights strung across the walls and ceiling. Modern juke joints were preceded by informal “jookhouses” that were actually tenants’ houses on plantations. Residents would clear the furniture from the largest room and spread sawdust on the floor in preparation for an evening, and often sold fried fish and homemade liquor to those who gathered for music, dancing, and gambling. Such gatherings were called house parties, fish fries, country suppers, Saturday night suppers, balls, or frolics. Many musicians recall first hearing blues at jookhouses run by neighbors or family members. Some artists, including Muddy Waters, ran their own jukes in Mississippi. In the 1930s coin-operated phonographs became widely distributed throughout the South and quickly became known as “jukeboxes.” Since that time, most music at juke joints (including Po’ Monkey’s) has been provided not by live performers but by jukeboxes and, later, by deejays.

The term “juke”—sometimes spelled “jook” and often pronounced to rhyme with “book” rather than “duke”—may have either African or “Gullah” origins, and scholars have suggested meanings including “wicked or disorderly,” “to dance,” and “a place of shelter.” Used as a noun, “juke” refers to small African American-run bars, cafes, and clubs such as Po Monkey’s; as a verb, it refers to partying. Variations of “jook” first appeared on recordings in the 1930s, and at a 1936 session in Hattiesburg the Mississippi Jook Band made what were later described as the first “rock ’n’ roll” records. “Juke” gained widespread recognition in 1952 as the title of a hit record by blues harmonica player Little Walter. More formal establishments in towns and cities eventually replaced most rural juke joints, but jukes continued to occupy an important place in the imagination of blues fans and performers. In the 21st century Mississippians Little Milton, Lee Shot Williams, Bill “Howlin’ Madd” Perry, and Johnny Drummer sang and composed new songs about jukes, and in 2004 Clarksdale established an annual “Juke Joint Festival” to celebrate the city’s down-home venues. content © Mississippi Blues Commission

Boyle

Peavine Branch - Boyle

The "Peavine" branch of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad met the Memphis to Vicksburg mainline at this site. From the late 1890s through the 1930s, the "Peavine" provided reliable transportation for bluesmen among the plantations of the Mississippi Delta. Charley Patton made the branch famous through his popular "Pea Vine Blues."

Prior to the late 1800s, most of the Mississippi Delta region was covered by swamps, thick forests, and canebrakes. Early plantations were established in areas less prone to flooding, and lumber companies used the Delta’s waterways to transport their products to the Mississippi River and on to distant destinations. However, these efforts were complicated by flooding, seasonal shifts in water levels, and the need for expensive dredging.

A solution came in the form of railways, which were first introduced in the 1870s and criss-crossed the Delta by the early 1890s.The railway system allowed cotton production to flourish, with many plantations served by small lines. One of these was the Kimball Lake Branch, known locally as the "Peavine Branch," which bluesman Charley Patton saluted in his 1929 Paramount Records recording, "Pea Vine Blues." The Peavine, originally two narrow-gauge lines run by local entrepreneurs–including a lumber company in Boyle–was taken over in the late 1890s by the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Company (called the Y&MV).

The line ran from Dockery Plantation, where Patton lived, and then ten miles west to Boyle, where it connected with the "Yellow Dog" (the local slang name for the Y&MV line), which led to Cleveland and points beyond. The term "peavine" was commonly used for railways that followed indirect routes, resembling the vines of the pea plant. Wisconsin-based Paramount Records’ advertising department used a drawing of an actual pea plant to promote Patton's record.

"Pea Vine Blues" is one of many blues songs about railways–a popular metaphor for escape as well as the primary means by which African Americans left the South during the Great Migration. The song’s meaning was clear to Delta residents, but obscure to others. Patton's song inspired other recordings on the "peavine" theme by artists including John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Williams, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Charlie Musselwhite, and Rory Block, among others. The leading Japanese blues record company named itself P-Vine Special in 1975 and reissued all of Patton's recordings on CD in 1992. content © Mississippi Blues Commission

|

| Ground Zero Blues Club |

|

| Bill Abel |

|

| Mein alter Sticker von 20011 war noch da! |

|

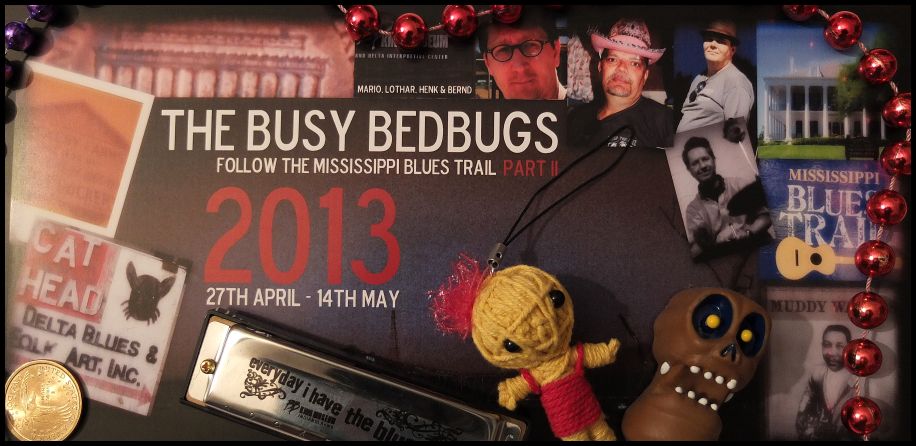

| Die Postkarte von THE BUSY BEDBUGS von 2011 war zwar überklebt, aber noch erkennbar. |

|

| Und wieder neue Aufkleber dran... |

|

| Mississippi Campfire!! |

Red`s Lounge

|

| Robert Belfour |

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen